Gothic Monasteries of Castile: Silent Guardians of History and Art

In the heart of Spain, far from the crowded boulevards and glittering façades of modern cities, lie the austere yet magnificent Gothic monasteries of Castile. These stone sanctuaries have withstood the tides of time, preserving within their cloisters the memory of medieval devotion, power struggles, and cultural flourishing. Despite their often remote locations, these monasteries remain critical to understanding the spiritual and historical identity of the Iberian Peninsula.

Architectural Legacy of Monasteries Like Uclés and Valbuena

Monasterio de Uclés, often dubbed the “Escorial of La Mancha,” is a monumental reminder of the influence of the Order of Santiago. Its evolution from Romanesque to Gothic and finally Herrerian styles illustrates the layered history of Castilian religious architecture. Constructed in the 12th century, the monastery served both spiritual and military purposes, its fortifications reflecting the turbulent Reconquista era.

In the north of Castile, the Monasterio de Santa María de Valbuena stands as a serene example of early Cistercian Gothic. Built in the 12th century along the banks of the Duero River, its austere façade conceals finely sculpted capitals and pointed arches—hallmarks of the Gothic aesthetic. Unlike more ornate monasteries, Valbuena’s simplicity reflects the Cistercian pursuit of purity and divine clarity.

Both monasteries have undergone careful restorations, ensuring their survival into the 21st century. They now serve cultural roles: Valbuena houses the Fundación Las Edades del Hombre, while Uclés offers educational tours and historical exhibitions. Yet, they remain solemn places, where each stone speaks of faith, perseverance, and artistic intent.

Spiritual and Political Influence in Medieval Castile

During the Middle Ages, these monasteries were far more than places of prayer. They functioned as centres of regional governance, education, and diplomacy. The monastic orders—particularly the Cistercians and the Order of Santiago—held vast estates and political sway, advising monarchs and managing vast networks of agricultural production.

The monks not only transcribed texts and scriptures but also influenced royal decisions. Uclés, in particular, became the spiritual capital of the Order of Santiago, whose members defended Christendom while administering lands and justice. Monastic leadership often intersected with secular power, forging alliances that shaped Castilian policies for centuries.

This dual role of the monastery—spiritual and administrative—cemented its importance in the medieval landscape. It offered a structured refuge during times of political instability and a centre of ethical and theological debate amid cultural change.

Artistic Treasures Hidden Behind Cloistered Walls

Castilian Gothic monasteries are treasure troves of artistic heritage, housing artefacts that span centuries. Frescoes hidden in private chapels depict scenes of martyrdom and salvation in vivid tempera. At Valbuena, recently uncovered wall paintings reveal the evolution of Gothic iconography, while fragments of polychrome adorn forgotten crypts.

Tombs of knights, abbots, and noble patrons are sculpted in marble and alabaster, often adorned with heraldic symbols and biblical scenes. These sepulchres reflect the transition from Romanesque rigidity to Gothic realism. In Uclés, the tomb of Juan de Padilla stands as a testament to 16th-century funerary art influenced by Gothic and Renaissance elements alike.

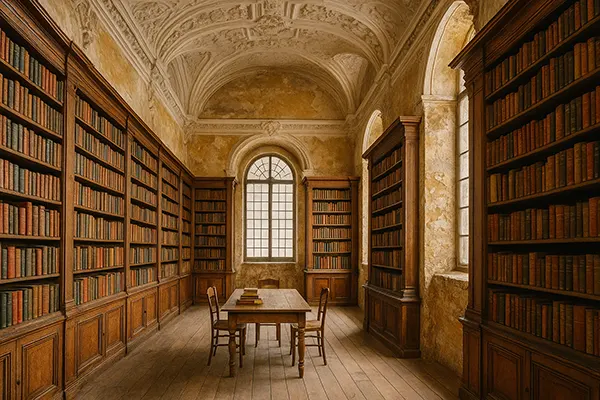

Monastic libraries also deserve mention. These repositories once contained priceless codices, illuminated manuscripts, and theological treatises. Though many were dispersed during secularisation, remnants can still be found within reconstructed archives, preserving the intellectual legacy of these religious communities.

Art as a Reflection of Ideological Identity

Monastic art was not merely decorative—it conveyed religious, moral, and political messages. Every sculpture, fresco, and illuminated page had pedagogical intent. They were tools of devotion and instruction in an age when literacy was limited to the clergy and nobility.

Architectural motifs, from ribbed vaults to stained glass, were calculated to elevate the mind toward the divine. The physical design of monasteries, with cloisters forming contemplative quadrangles, embodied theological ideals of order, humility, and cosmic harmony.

This artistic language extended Castile’s self-image as a bulwark of Christianity and royal piety. The visual culture of these monasteries continues to offer invaluable insights into the religious psyche of medieval Spain, shaping national heritage beyond mere aesthetics.

Why These Monasteries Still Matter Today

Despite their monumental significance, many Gothic monasteries in Castile remain overshadowed by Spain’s more prominent landmarks. Their rural isolation contributes to this neglect, yet this very remoteness preserves their authenticity and aura. Visiting them is less about spectacle and more about encounter—with silence, with history, with enduring faith.

These monasteries offer lessons in sustainability and adaptive reuse. Some have been converted into cultural institutions, others into quiet retreats for scholars and artists. Their preservation is vital, not only for historical study but also as spaces where past and present can engage in dialogue.

They challenge modern Spain to reconsider its roots—how communities organised around shared beliefs, how art and governance interwove, how silence could hold more meaning than proclamation. In a time of digital saturation, the monasteries of Castile stand as meditative counterpoints, inviting reflection grounded in centuries of lived experience.

Guardians of a Forgotten Heritage

These Gothic monasteries may not command headlines or tourist rankings, but they are no less integral to Spain’s story. As archives of sacred art, political history, and architectural evolution, they offer a multi-dimensional view of Castilian life across the ages.

Each monastery, from Uclés to Valbuena, guards secrets waiting to be understood—inscriptions, relics, and murals that reveal how spirituality, power, and art coexisted. Their remote locations do not diminish their relevance; rather, they heighten the intimacy of their encounter with history.

By valuing and preserving them, Spain acknowledges not just its Catholic legacy but also its layered, pluralistic past. These Gothic sites are not relics of superstition or faded grandeur—they are enduring symbols of introspection, resilience, and cultural continuity.