Mérida in One Day: Roman Theatre, Amphitheatre, and How to Read a Roman City

Mérida (ancient Augusta Emerita) is one of those places where you can stop treating Roman remains as separate “sights” and start reading them as parts of a working city. In a single day you can follow a logical storyline: entertainment buildings that organised people by status, a river crossing that controlled movement and trade, water engineering that made dense urban life possible, and a museum that helps you put names and functions back onto the stones. This route is designed as a script you can actually walk: Theatre → Amphitheatre → bridge/aqueduct → museum, with specific things to look for at each stop.

Stop 1: Roman Theatre — how the building tells you who mattered

Start early at the Roman Theatre, because the first impression matters: the scale is not only architectural, it is social. The cavea (seating bowl) is a diagram of hierarchy. The lower rows closest to the orchestra were for the local elite; the higher you go, the more the experience changes — more distance, more exposure, less prestige. When you stand in the orchestra and look up, you are looking at a crowd arranged as an argument: “this is the order of the city”.

Next, look at the stage architecture (the scaenae frons) as a piece of messaging. In Roman theatres, the stage wall is not a neutral backdrop: it frames the actors with columns, niches and statues, turning performance into civic theatre as well. Even if some elements are reconstructed, the overall effect is clear: the city used stone and symmetry to project stability, wealth, and a connection to Rome itself.

Finally, pay attention to circulation. Vomitoria (the entrances and exits that feed the seating sectors) are practical engineering, but they are also crowd-control. They keep the audience moving in a predictable way, and they help separate groups. A useful exercise is to walk the perimeter and count how often your view is guided or blocked. Romans did not just build a place to watch a play; they built a machine for managing people.

Stop 1, closer look: acoustics, sightlines, and what the audience actually experienced

Acoustics in Roman theatres are often described in a single sentence, but the real point is how sound supports authority. A well-projected voice makes the actor “larger” than the crowd, and it makes the text feel official. Try this simple test: stand on the stage line and speak at normal volume while a friend walks up into the middle tiers. Even with modern visitor noise, you can still sense why live speech could command attention without amplification.

Sightlines are equally revealing. The Theatre is designed so the majority can see the action, but not everyone sees it equally. The best lines are rewarded to the most important spectators; the compromises are pushed upward. That is not a flaw, it is policy. If you want to “read” the building, choose three viewpoints — low, mid, high — and note what changes: how much of the stage you lose, how faces become gestures, how the experience becomes more collective and less intimate.

Before you leave, take a minute to connect the Theatre to the city around it. Roman entertainment buildings were not isolated theme-park attractions; they sat within an urban system of streets, squares and services. Your next stop, the Amphitheatre, is only a short walk away for a reason: the city clustered mass venues where crowds could be managed, supplied, and moved along without chaos.

Stop 2: Amphitheatre — the city’s taste for spectacle, written in stone

The Amphitheatre changes the story from civic culture to controlled violence, but it keeps the same Roman habit of organising people. Start by locating the arena and its boundaries. The shape, the barriers and the access points exist to protect the audience and to control what enters and exits the performance space. In practical terms, the arena is a stage that must withstand movement, impact and rapid changeovers.

Now read the seating as a second lesson in social order. The closer sectors again reflect privilege, but here the psychology is different: proximity is part of the thrill, and therefore part of status. The building also has to handle a more intense crowd response than a theatre. That is why circulation, separation and sightlines matter even more: a Roman amphitheatre is both spectacle architecture and risk management.

Finally, imagine the operational side. Events required staff, animals, equipment, and timing. Even without seeing every internal space, you can infer the logic: quick entrances, quick removals, and clear routes that keep performers and animals away from the wrong corridors. When you stand at an entry point and look at how it funnels into the arena, you are seeing a Roman solution to a very modern question: how do you run a mass event safely and efficiently?

Stop 2, closer look: how to connect the Amphitheatre to the rest of the day

Use this stop to widen your “city reading” beyond entertainment. Ask two questions: where did the water come from, and how did people cross the main river? Those are the two infrastructural answers that underpin everything you have seen so far — crowd comfort, public baths, fountains, cleaning, construction, food supply, and movement of goods. Mérida gives you strong evidence for both.

From here, aim for at least one major piece of infrastructure outside the ticketed venues. The Acueducto de los Milagros is a good choice because you can experience it at ground level, and because it still dominates the landscape enough to explain its purpose without a guide. It also sets up the museum visit: once you have seen the big engineering, the small objects and inscriptions in the galleries feel less abstract.

If you have the time and energy, add the Puente Romano over the Guadiana as a second infrastructure “chapter”. A bridge is not just a crossing; it is a controlled entry into the city, a place where movement can be measured and taxed, and a line that shapes how neighbourhoods grow. Even a short walk along the bridge helps you sense why Roman cities were often planned around strong, durable crossings.

Stop 3: Bridge and aqueduct — the hidden system that made the city work

Start with the Puente Romano if you want the broadest sense of scale. Standing on a long Roman bridge is a reminder that empire is also logistics. A durable river crossing keeps trade routes reliable, connects farmland to the urban core, and makes troop movement predictable. It also tells you the city’s priorities: Mérida is not only a place of monuments, it is a place that had to function daily as a provincial capital.

Then move to the Acueducto de los Milagros to read Roman water strategy. The aqueduct is not “just arches”; it is a line that implies a source, a gradient, maintenance points, and a final distribution system inside the city. When you look at the remaining piers and arches, you are seeing the visible fraction of a much larger network. Romans invested in water because water multiplies urban capacity — sanitation, baths, fountains, and industries all depend on it.

Practical tip for the day: treat these two stops as a reset for your eyes. After theatre seating and arena boundaries, infrastructure might feel quiet, but it is the part of the story that explains endurance. Entertainment buildings show values and social structure; the bridge and aqueduct show what the city had to guarantee every day to keep those values and that structure stable.

Final stop: National Museum of Roman Art — turning stones into meaning

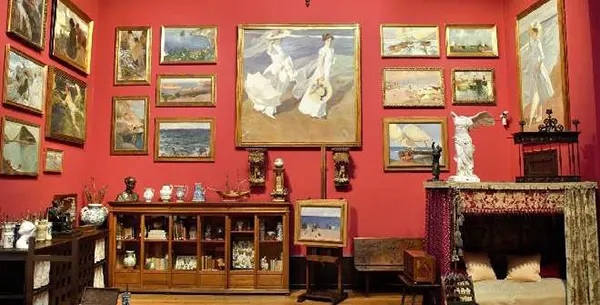

Finish at the Museo Nacional de Arte Romano (MNAR) to give the day a solid “decoder ring”. The building itself is part of the experience: it is designed around height and rhythm, which suits Roman sculpture, inscriptions and architectural fragments. Focus on objects that answer the questions you built up outdoors: who paid for these public works, who benefited, and how did people describe their own city in writing and images?

Look for inscriptions and portraiture as your fastest way into social reality. Inscriptions are blunt: names, offices, dedications, and sometimes the budget logic of public generosity. Portraits show how the local elite wanted to be seen — clothing, posture, idealised features. After seeing the Theatre and Amphitheatre, these objects stop being “museum pieces” and start feeling like the cast list and funding credits of the city.

End with everyday life: mosaics, domestic items, religious objects, and anything linked to water use or public bathing. This is where “reading the city” becomes personal. You have walked the spaces where crowds gathered; now you can connect that public life to private routines and beliefs. If you leave with one mental model, make it this: Mérida’s Roman remains are not a scattered set of ruins, but a coherent urban system you can still trace on foot in a single, well-planned day.